Al Capone’s been going to pieces lately…

In Sacramento, California, Capone’s granddaughters have announced they are selling off many of their grandfather’s personal items from his Florida home at 93 Palm Beach in Miami Beach, in part due to fears of encroaching California wildfires.

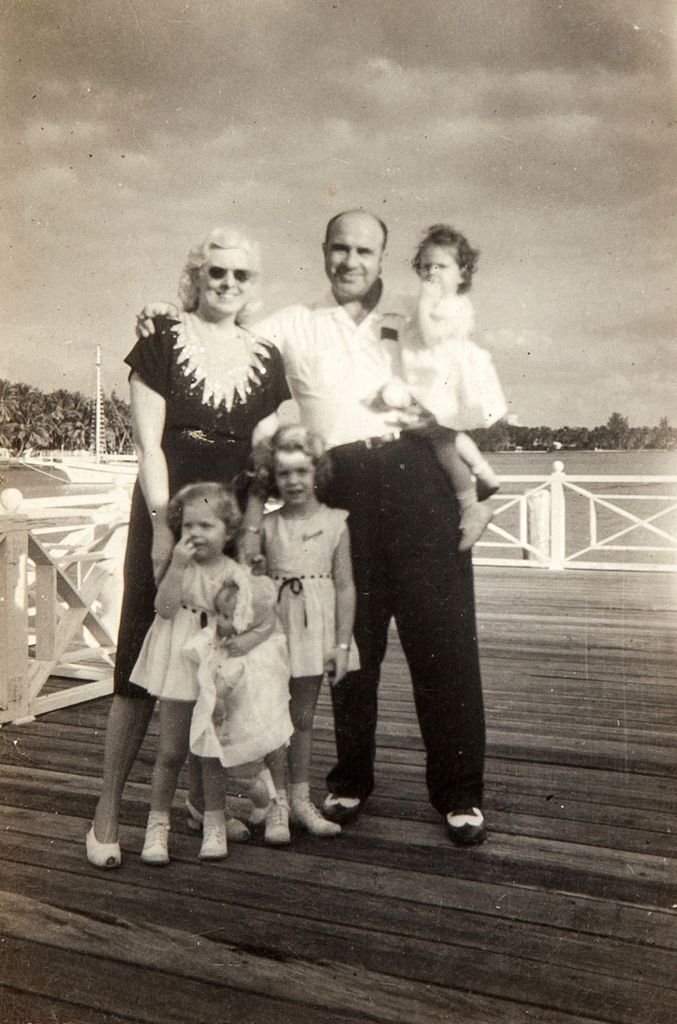

Diane Capone, one of Capone’s three granddaughters, lives in Auburn, CA, which is currently near one of the major wildfires devastating California. A fire in Diane’s home would put a majority of the collection at risk, so Diane and her sisters decided it was time to sell. “It was a tremendous relief for the memorabilia to be removed because there’s no way we could save it…all,” Diane told The Washington Post. The fires are so bad this year that they can smell smoke from their porch. “This is the second summer we’ve had our suitcases packed in case we were going to be evacuated, and we knew there was no way we could save these things that belonged to our grandparents.” Something, then, had to be done with the memorabilia fast. Besides the fires, the sisters aren’t getting any younger, either. Diane, the oldest, is 77, and the three of them wanted to make sure they could still provide the proper context and stories for each item before they’re turned over to collectors and museums.

The auction will be held by Witherell’s, a respected Sacramento auction house. Brian Withrell, the house’s director, is a frequent appraiser on PBS’ Antiques Roadshow. According to him, Al’s memorabilia will be the largest auction of Al’s personal item ever, as well as one of the largest mob-related auctions in general. The last auction of Al’s stuff was in 1992. The auction will be held LIVE online by Withrell’s on October 8th, 2021, so anyone with an internet connection can attend.

According to the Chicago Tribune, starting bids on items range from as low as $100 to as high as $50,000—so if you have at least one hundred dollars, you too could own a piece of Al! Personally, that seems surprisingly affordable for a major auction like this.

WHAT’S FOR SALE

The auction, which is entitled “A Century of Notoriety: The Estate of Al Capone,” features around 174 items that relate to Capone’s life, most of which are from the late 1920s. Here are a few of the collection’s most interesting highlights:

“Sweetheart,” supposedly Al’s “favorite gun,” was used “only used in self-defense,” Diane claims—if it was ever used at all. Either way, the starting bid is $50,000.

A diamond encrusted monogramed watch, with an estimated worth of $25,000-$50,000. The auction features many other diamond encrusted items as well, all marked with the initials “AC”, including a pocket knife, a match holder, a belt buckle, and many more. These kind of extravagant items help prove that rather than sock his money away as some legends claim, Al liked to spend his money, and spend big—an aspect of his life that was heavily evidenced at his trial as well.

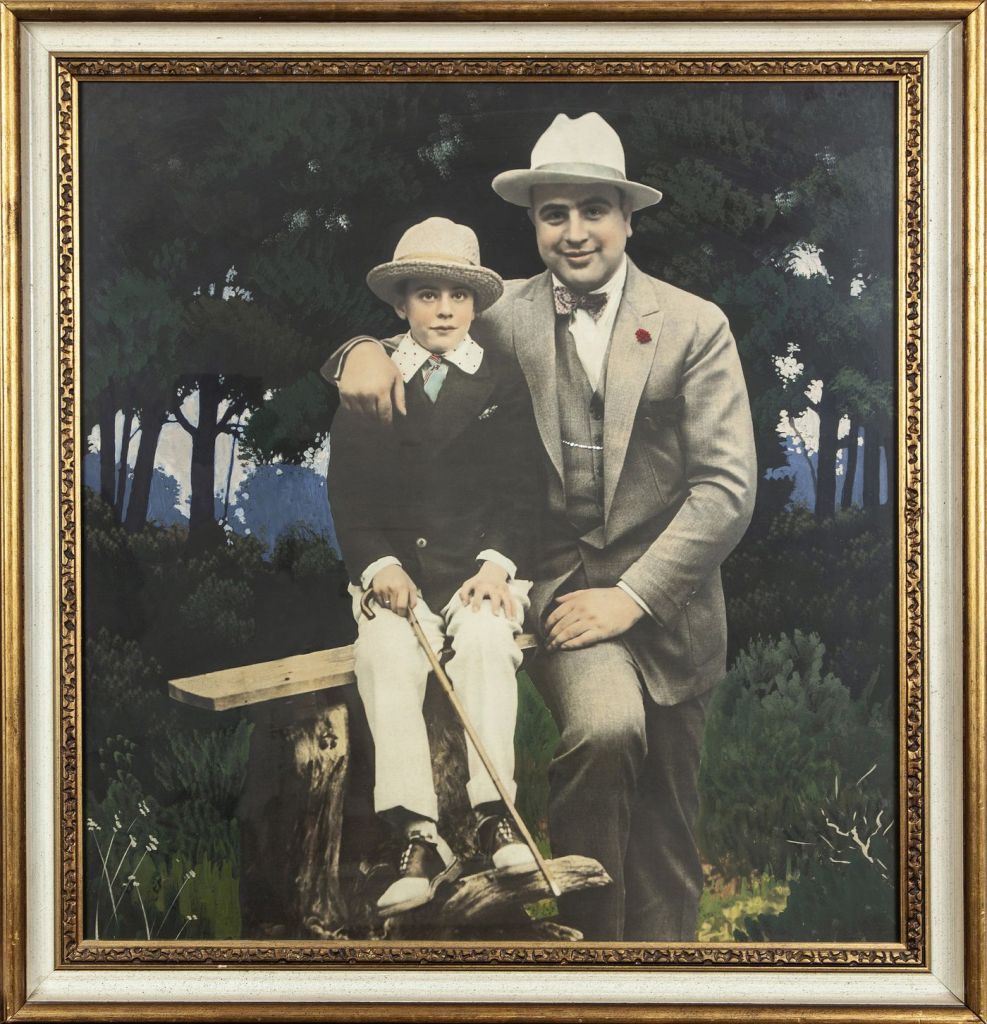

Various family photos, including this framed photo of Al with his only child, Sonny, are a large part of the auction as well, and help to show a softer side of Al—the devoted, loving man that his family knew and loved.

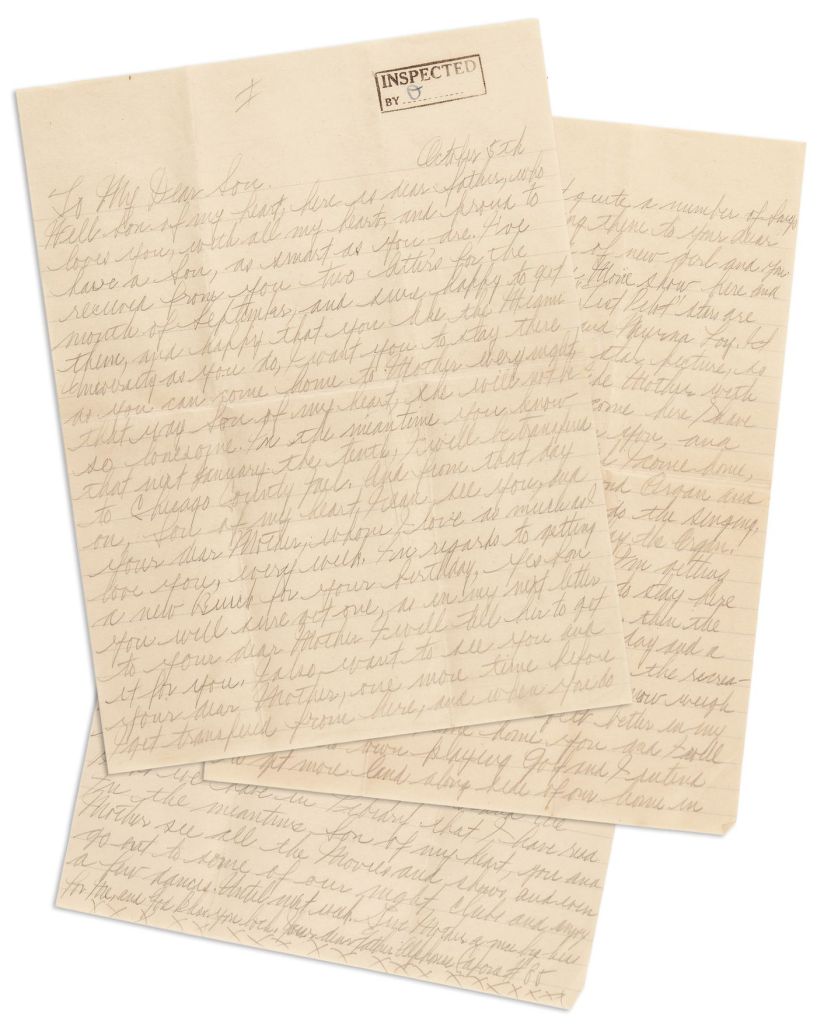

A personal letter from Al to his son Sonny is particularly insightful. “Over and over and over again, he refers to my dad as ‘son of my heart’ and that’s not the language or the words of a man who is hard-hearted,” Diane Capone told CBS News. “Those are the words of a man that is a very devoted father and that is the part of the story that we wanted to tell.”

While the majority of items are expected to go to private collectors, museums may bid as well. Currently one of the most famous Al-related item which can be seen in a museum is the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre brick wall at the Las Vegas Mob Museum. The Chicago History Museum can’t afford to bid, but it’s hopeful that any collectors who purchase these items might donate them to the museum. “We do have people who who step forward and acquire material like this and then donate it to the museum because they know that what should happen to important historic local artifacts is they should end up in a public institution so people can have access to them,” said John Russick, senior VP of the Chicago History museum. Personally, I hope someone does, as it’s surprising to think that they don’t have a personal item of Al’s, seeing how important he is to Chicago’s Prohibition history.

GRANDAUGHTERS WANT TO CHANGE PUBLIC’S VIEW OF “PAPA” CAPONE

While the flashy diamond-encrusted items and guns represent Al’s larger-than-life public persona, it’s the multitude of family photos up for auction which his granddaughters hope will display a very different side of Al—the one they hope more people will keep in mind when they discuss their grandfather.

Diane, who can still remember her grandfather, recalls a generous and caring man who loved his family very deeply. She recalls him reading to her, playing with her, and taking her on walks in her grandmother’s garden when she was a toddler, holding onto his finger with her tiny hand. The strongest memory she has of Al, however, is when he died: “The day that he died we were taken, my older sister and me, upstairs to his bedroom and my father lifted us up to the bed so we could kiss him. I remember Papa looking at me and he just said, ‘I love you, baby girl.’ That is a memory that has been with me since I was 3 years old and I will never forget it as long as I live.”

The contradiction between these two sides of Al—the flamboyant kingpin who oversaw a blood-soaked Chicago crime syndicate and the loving family man—is something his descendants still contend with today. In her memoir Uncle Al Capone: The Untold Story From Inside His Family, Dierdre Mae Capone, granddaughter of Ralph Capone and Al’s grand niece, describes in vivid detail how Al’s legacy affected her and her family, from other children shunning her in childhood for being a “mobster’s daughter” to Chicago employers firing her as soon as they discovered her heritage—and she also tries to reconcile the loving family man she knew with the legendary criminal. Diane felt this legacy as well, as did her father, Sonny Capone, Al’s only child. In an interview with Yahoo! News, Diane says her father “gave us little suits of armor so we were able to handle” the insults and misconceptions which came from being part of the “tremendous chasm” between Al’s public and private lives. As she told The Washington Post, “how is it possible that a man who was so loving and so generous and so devoted could have been capable of some of these things that were alleged? I don’t know how to reconcile it, but I suppose I’ll have to wait until get to heaven, and I can find out then.”

In response to her experiences, and to correct what she saw as the “grossly inaccurate” picture most people have of her grandparents, Diane wrote Al Capone: Stories My Grandmother Told Me. In a similar vein to Dierdre’s memoir, it contains many personal family stories about Al, particularly those relayed by Mae Capone, Al’s wife. Diane is working on a second book as well, called The Capone Girls, which explains what happened to the family after Al died and how his legacy affected them. Both authors hope their books, just like the collection their family is now sharing with the world, will show people the softer, human side of Big Al.

Want more photo’s of Al’s stuff? Try this Chicago Sun Times article, this Chicago Tribune article, or visit the online auction itself at Witherell’s website. And if you’re thinking of buying a piece of Al for yourself, you may want to consult the memorabilia buying guide at My Al Capone Museum. The owner of the site is a collector and has a lot of advice for those looking to buy, especially regarding fakes/questionable items. Witherell’s, however, has taken great pains to make sure the provenance of their items in this auction are unimpeachable, and have included signed statements from Capone’s granddaughters with each item, so there’s no need to worry about their authenticity.

~*~

Unfortunately, just as his legacy is being cast in a different light, Al’s historic Florida residence may be about to disappear.

Al Capone’s Florida home at 93 Palm Avenue in Miami Beach, where he lived and eventually died in 1947, had been on the market for quite a while until this summer, when it was purchased for $10.57 million by a pair of developers. New owners Todd Glaser and Nelson Gonzalez plan to demolish it to make way for a “two-story modern spec home with 8 bedrooms, 8 bathrooms, a Jacuzzi, spa and more.” They then plan to resell the property once the new house is built for $45 million.

The current property is “a piece of crap,” says owner/developer Todd Glaser, and “a disgrace to Miami Beach”—partially due to the fact that it has “flood damage and standing water,” but mostly thanks to Al’s notorious reputation. Glaser says Al’s connection to Miami Beach is “not something to celebrate”, putting Glaser in line with how many Chicagoans have felt about the possibility of Capone’s Chicago home being turned into a museum. He considers it akin to preserving “Confederate statutes,” and that it would become a “divisive symbol” for the community. He also thinks it’s not worth saving due to it’s age: “it’s not worthy of being saved because it’s lived its life. The house is 100 years old,” he told The New York Times. The home was restored to its former glory, however, in 2014 by architecture firm MB America, and as these pictures attest, it doesn’t look as if it’s deteriorated too much in that time.

Here are some pictures of the house. Does this look like a “piece of crap” to you, dear readers? 😉

The city of Miami Beach, however, may feel differently. The city is currently toying with idea of giving it a historic designation, and local historians are all for it. “[Al] wasn’t a saint by any means…but, at the same time, we think his home is a part of the history of our city: the good, the bad and the ugly. And we don’t think it should be torn down and replaced with a McMansion.” Quote from Daniel Ciraldo, director of the Miami Design Preservation League, a non-profit devoted to preserving significant structures in the city. And Capone’s story isn’t the only one his home is telling, says Ciraldo. It also displays “the pioneering spirit of the early developers and the citizens of this town.” “Do we just want this story to be just in a book on the shelf, or do we want to preserve this living, breathing structure that connects us to so many parts of our history?” Ciraldo asked in an interview with the Miami New Times.

Glaser has offered to sell the place as-is for $16.9 million, extensive water damage included, but it’s unlikely that non-profits like Miami Design will be able to produce that much to purchase the home, much less repair it to the point of becoming a historic site or museum.

A public meeting with Miami Beach Historic Preservation Board supposedly occurred on September 15th, 2021 which allowed local residents to voice their opinions, but I have been unable to find the results of this meeting. Prior to the meeting, the Board seemed to consider the home worthy of preserving thanks to meeting “multiple criteria” for preservation, three of which at least must be met in order for it to be considered for preservation. To begin with, 93 Palm “embodies the distinctive characteristics of the historical period,” such as the Spanish stucco and arches and the Art Deco interiors. It also is associated “with events that have made a significant contribution to the history of the city, the county, state or nation.” Al’s house was well-known during his life, and even his naysayers must admit that he was an important part of Prohibition history, and had an impact on Miami’s criminal history as well during his residence. Al’s fame also guarantees the last criterion, an “association with the lives of persons significant in the city’s past history.” While Al wasn’t part of Miami’s history for his whole life, he certainly made an impact, and the rest of the country was well aware of his residence there, and how he managed to control his Chicago empire even from sunny Florida. As the Miami Herald argues, Al is indeed emblematic of the gambling, booze-soaked Miami Beach history during the 1920s, “a bloody, greedy era” which exists whether Floridians want to acknowledge it or not.

As a result, the Board feels the demolition of the home would be “a substantial loss to the social, cultural and environmental heritage of our community,” and may designate it as a place of historic interest. If they do, that may make it harder for the developers to go ahead with their plans to bulldoze. If you’re interested in adding your voice to this issue but don’t live in Florida, there is an online petition at Change.org which you can sign.

Glaser currently claims he has “tremendous” local support for not preserving Al’s home, saying that it does not “deserve remembrance,” and that he is afraid—along with many of the neighboring residents which he’s talked to—that if preserved, the home will turn into some kind of “godawful tourist trap.” Local residents during the 1920s, 30s, and 40s would have agreed: none of them wanted Al living near them, either.

Florida was Capone’s last stop on his nationwide tour for a new home. The city was one of many he’d perused after declaring to reporters in 1927 that he planned to “abandon…the bootlegger’s trade…[and] abandon…Chicago,” claiming he was “sick of the job” and wanted out of the business entirely (Bergreen, 261-262). Al’s sudden need to get out of the trade probably wasn’t helped by the fact that police chief O’Connor had declared he would arrest him the second he stepped foot back in Chicago. Unfortunately for Al, the local police were waiting for him everywhere he went. Los Angeles’ chief of police James E. Davis told him that he was “not wanted here” and gave him twelve hours to leave the city (265). In Joliet, IL, he was met by “six policemen fixing him in the sights of their shotguns” (Ibid).

By January 1928, though, he’d set his sights on Miami and was determined not to be run out of town. To that effect, then, he went straight to Leslie Quigg, Miami’s chief of police: “Let’s lay the cards on the table. You know who I am and where I come from. I just want to ask a question. Do I stay or must I get out?” He had already been “hounded,” he said, “when somebody heard I was in town. All I have to say is that I’m orderly. Talk about Chicago gang stuff is just bunk.” Declaring that “I am going to build or buy a home here and I hope many of my friends will join me…I will even join your rotary club,” Al dug in his heels and asked around about property (265). He was immediately swarmed with offers—the Miami real estate boom didn’t care who he was—but the city’s elected officials pushed back, declaring they’d never allow it (Ibid). Eventually, Capone had a sit-down with them and said he wasn’t leaving, so Miami mayor J. Newton Lummis convinced Capone to get a home in nearby Miami Beach instead—and he agreed to help him (269). Apparently, Lummis figured that if Al was buying real estate, he should be the one to help facilitate it, especially if he got a cut of the sale, so he had his son, Parker Henderson, buy the property using Al’s money, then transfer the property deed to Mae, Al’s wife. That way, there was supposedly no paper trail leading to Al. Henderson was young, impressionable man who was attracted to the gangster life, and he was thrilled when Al gave him a diamond studded belt buckle and was equally happy to help him purchase a home (271).

Al found the home ideal for his purposes, as it was easily defended thanks to its island location while still having a strong “millionaire” (271). Capone’s home was fortified with cars full of guards, high walls, lots of flat ground with no trees or cover for enemies to hide in, and “every precaution taken to see that the gang chieftain can enjoy himself in safety” and “luxurious comfort.” Aside from adding the 30 x 60 foot pool, a rock fish pond full of tropical fish, a pool cabana, an extra dock, and thicker concrete walls, Capone also built a gatehouse with a telephone to screen visitors. The fact that the home had been previously owned by another fellow who’d made his fortune in liquor may have made it attractive to Capone as well. Originally built for Clarence M. Busch of Anheauser-Busch fame in 1922 by architect W. F. Brown, the home already had an association with the liquor trade.

His neighbors, though, didn’t appreciate Capone’s guards. Nearby homeowners complained that they regularly saw “men walking around the Capone grounds with pistols in their pockets or strapped to their hips,” that he harbored “dangerous” people from Chicago, and that they didn’t “want to live…among gangsters.” Al was often forced to beef up his security, however, especially when things got hot in Chicago. Al was in Florida when the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre went down, and after that, his crime life and family life started to intersect to the point where he “created a spectacle everywhere he went,” whether he wanted to or not (287).

Initially, such complaints about Al fell on deaf ears. During the 1920s, Miami Beach was still developing as a community, and after the real estate boom fizzled out, it desperately needed “support from men with deep pockets” (270). Locals couldn’t afford to be choosy about who moved in, much less who wanted to be a part of the local social scene, as at that time society was “whatever people said it was”—so Capone couldn’t be fully excluded no matter what (Ibid).

Sources conflict, however, on just how much Al wanted to be a part of that society.

Laurence Bergreen, author of Capone: The Man and the Era, insists that both Mae and Al desperately wanted social acceptance from their fellow Miamians. Mae decorated the Palm home “with a vengeance,” going on a “furious spending spree” which favored French styles and lots of silver and gold, items Bergreen called “devoid of taste, reeking of money…the kind of opulent décor that the wife of any newly rich magnate might be expected to purchase,” with the ultimate hope to ingratiate them into the local social scene: “to the extent that respectability could be bought, Mae did so” (283). Mae also tried to actively manage their public image, says Bergreen. She was known for being overly generous when she was afraid she’d offended someone, and once paid a neighbor with a $1000 bill for a $500 long distance telephone bill (284). The Capones never got the social acceptance they craved, though, because Al’s “career as a racketeer made ordinary human relationships all but impossible” no matter how much money he threw around (288).

Author Johnathan Eig disagrees, however. “He and Mae did not try to become part of the upper crust,” says Eig in Get Capone (Eig, 134). It was “a sign of Capone’s humble roots that he…didn’t imagine that he belonged, suddenly, in high society,” and thus made no real attempt to enter it, instead using his giant patios and his pool to entertain visiting friends and associates from Chicago (Ibid). A 1929 Tribune article claims Capone was “a gracious and affable host, anxious only to please those who accepted his hospitality” and not a “troublesome neighbor,” whom many, “if they did not know him by reputation…would simply set him down as a quiet man with rather curious tastes” and a penchant for keeping guards around.

A handful of newspaper articles—plus some trial testimony—indicates that Al may have tried, at least initially, to horn his way into local social circles. In May 1930 Capone held a banquet for fifty hand-selected “prominent residents,” complete with “hand-graved invitations,” and designed to encourage “good-will” among the locals. When local residents later attempted to have Al’s home padlocked (more on that in a minute), many witnesses testified to attending lavish parties that he threw at his Palm Beach home. Another witness, R. R. Burdine, president of the largest department store in Miami, claimed that he’d been approached by Al’s men, who suggested he “sponsor” Al’s entry into Miami society by hosting a party where Al could meet the local elite. Though he admitted talking to Capone whenever he entered his store, Burdine didn’t agree to host the party, claiming that, “I knew I could not count Capone among my friends, who would not have stood for it. If I did I would be severely criticized,” and blamed for helping to foster elements in Miami Beach there were “dangerous to society.”

Whether Al wanted social acceptance or not, though, it was becoming increasing clear that Miami’s prominent citizens didn’t want him around. As soon as they found out he was moving in, prominent Floridians moved to stop him. “Al Capone must get out,” trumpeted a 1928 Chicago Tribune article writing from Miami Beach. “This was the ultimatum delivered to city and country law enforcement…by a delegation of Palm Island residents who said they would not countenance the Chicago gang leader as a resident of Palm Island. Spurred to action by reports that Capone had acquired an expensive home…which he was remodeling into a permanent Miami headquarters.” When their declaration didn’t work, locals decided they could get Al arrested on Volstead violations instead, and encouraged Miami police to raid his home. When Al went out of town in March of 1930, policemen raided his Florida estate and found “eight stacks of whiskey and champagne and other wines” in a locked room upstairs.

Merely finding liquor in one’s home wasn’t enough, of course, to violate the Volstead Act, so locals went on to sue Al and attempted to lock him out of his own home. Concerned citizens approached Miami state attorney Vernon Hawthorne, asking him to permanently padlock Al’s estate, claiming it was a “public nuisance” and “the scene of repeated liquor violations,” and attracted all manner of “law violators” and other undesirables. The trial that ensued led to a lot of testimony about boozy parties, local corruption, and citizen’s general anger at having their local community overrun with visiting gangsters. Burdine, the department store owner, apparently attended at least one of Al’s parties, where he claimed he saw “plenty of liquor.” “It was very nice,” he testified; “Some drank Scotch, but champagne was served continuously. I saw a sink literally loaded with champagne, and it looked very attractive.” Burdine went on to roundly condemn Al and his ilk: “He is what we call a gangster. I think he is dangerous to society and the world at large…a man who kills when it is necessary, who carries his point with whatever weapon is at hand, who takes the law into his own hands, has no respect for law or decent society, who makes his own laws. He thinks nothing of human life or its sanctity.”

Burdine neglected to mention, however, that the reason he was there was that he’d been asked to attend the party on behalf of Miami’s finance community to convince Al to donate a $1,000 check to the community chest, which he happily accepted—until irate local citizens forced him to return it. It was clear that Al had some fingers in local politics already—especially given his connection with the mayor—and on June 13th, the state suddenly dropped the case against Al, and Al’s lawyer had it successfully dismissed. After that, no further attempts were made to forcibly remove Al from Palm Beach, though locals continued to complain, and Al lived out the rest of his days there until his death in 1947.

Al’s Florida home was also part of his downfall. Al’s attempt to hide his paper trail through Henderson didn’t work as well as he thought, and the purchase of 92 Palm Beach became a key part of Al’s 1931 trial. The monetary transaction of $80,000 in Western Union money orders used to purchase the home was traced directly from his gang headquarters in Chicago to Miami. The funds were sent under the alias Albert Costa, and Henderson flipped testified to the whole scheme, and it became another piece of evidence in the trial, more proof of Al’s lavish, untaxed spending. Whether they could trace the money or not, though, the house itself “proved that he enjoyed substantial income” to the IRS (Bergreen, 272-273).

The home is still a source of pleasant memories for Al’s family. Diane Capone and her sisters can recall spending many lovely summer afternoons there in the late 1940s with their grandmother Mae, who continued to live there until 1952. Mae moved into the guest house permanently and left the rest of the house alone, save for the large patios, which were used for massive family dinners. She refused to sleep in the master bedroom. When asked why, Mae said “I had such happy times there with Papa and he’s not there any more and I don’t want to go into that room any more.” The scent of gardenias still immediately transports Diane back to the time she spent there with Mae. While the pending demolition isn’t exactly welcome, Diane knows she’ll never lose her family memories: “That beautiful place, that paradise, will always be there in my heart.”

In the end, Miami’s citizens never managed to successfully remove Al from Miami Beach, and it’s possible they won’t be able to do so again. Whatever happens, though, Big Al’s legend will live on in Florida’s history no matter what. Maybe they should just make peace with it this time around…

~*~

Interested in learning more about Al’s time in Miami? Try this four part series from the Miami History blog: part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4. Part 1 in particular includes more about 93 Palm Beach.

~*~

Works Cited:

Bergreen, Laurence. Capone: The man and the era. 1994. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Eig, Jonathan. 2010. Get Capone: the secret plot that captured America’s most wanted gangster. New York: Simon & Schuster.

“AL CAPONE CALLS ON MIAMI CHIEF; FINDS SANCTUARY: CICERO CHIEF TIRED OF GANG TALK, HE SAYS.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Jan 11, 1928. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/al-capone-calls-on-miami-chief-finds-sanctuary/docview/180881198/se-2?accountid=3688

Kinsley, Philip. “EXPOSE CAPONE’S GOLD FLOW: HIGH SPENDING OF GANG CHIEF SHOWN IN COURT WIRING OF FUNDS TO FLORIDA TOLD. FLOW OF CAPONE RICHES TOLD AT TRIAL GOVERNMENT’S EVIDENCE REVEALS FLOW OF GOLD TO AL CAPONE AT MIAMI.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Oct 10, 1931. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/expose-capones-gold-flow/docview/181233252/se-2?accountid=3688

“Capone’s Fortified Florida Palace Awaits Chieftain: A Guarded Mansion.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Mar 16, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/capones-fortified-florida-palace-awaits-chieftain/docview/181050015/se-2?accountid=3688

“CAPONE ESTATE IS ARMED CAMP, WITNESS AVERS: FLORIDA SEEKS TO PADLOCK GANGSTER’S HOME.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Jun 12, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/capone-estate-is-armed-camp-witness-avers/docview/181140738/se-2?accountid=3688

“Capone Opens Florida Manor to the Gentry.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Feb 19, 1929. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/capone-opens-florida-manor-gentry/docview/180963030/se-2?accountid=3688

“DISMISS CAPONE CHARGE AGAINST MIAMI OFFICERS: GANG CHIEF PLANS SOCIAL DEBUT TONIGHT.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), May 28, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/dismiss-capone-charge-against-miami-officers/docview/181108053/se-2?accountid=3688

“Capone Wine Wasted on Miami Society.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Jun 13, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/capone-wine-wasted-on-miami-society/docview/181139843/se-2?accountid=3688

“MIAMI NEIGHBORS ASK OFFICIALS TO DRIVE OUT CAPONE.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), May 26, 1928. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/miami-neighbors-ask-officials-drive-out-capone/docview/180902677/se-2?accountid=3688

“FLORIDA RAIDS CAPONE’S RUM; SIX ARRESTED: GANG CHIEF’S WHEREABOUTS STILL A MYSTERY.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Mar 21, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/florida-raids-capones-rum-six-arrested/docview/181096074/se-2?accountid=3688

“FLORIDA SUES TO OUST CAPONE; FIGHT HIM HERE: CHICAGOANS ACT TO CURB HIS UNION POWER.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Apr 23, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/florida-sues-oust-capone-fight-him-here/docview/181091924/se-2?accountid=3688

“MIAMI TO KNOW TODAY IF CAPONE GOES OR STAYS: CITIZEN OR HOODLUM? COURT TO RULE.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Jun 14, 1930. https://www-proquest-com.glenviewpl.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/miami-know-today-if-capone-goes-stays/docview/181112789/se-2?accountid=3688