~*~

This year for Armistice Day,

why not read a WWI memoir

by a real war hero?

~*~

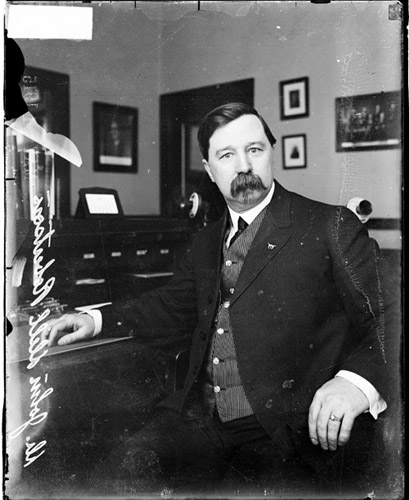

Arthur Guy Empey was an American soldier who served in the British Army during World War I and wrote a best-selling memoir about his experiences. Over The Top sold over a quarter million copies upon its release in 1917 and went on to top bestseller lists for the rest of the war years. It did so well, in fact, that not only did Empey’s book become one of the best war memoirs of its time, but it spawned a multitude of further careers for Empey as a lecturer, author, actor, director, songwriter and film producer.

~*~

While largely forgotten today, Empey’s book was considered one of the “best remembered of World War I books” as recently as 1945, and there is still much to recommend it as both a good read and for its unique insight into the war experience of the common solider. If you’re looking to do historical research on soldier’s daily life during WWI, Empey’s book is an excellent and entertaining place to start.

~*~

Here are ELEVEN reasons why you should read Guy Empey’s Over the Top on Armistice Day:

-1-

It was written on “the bleeding edge” of history,

which is rare for most war memoirs

Unlike most WWI memoirs, Over the Top was written—and published—during the Great War itself. This explains why many of the place names are redacted, why it offers some unique insights into America’s reaction to the early parts of the war. It’s unusual among war memoirs, as well, since most of them are written well after the war is over. Empey was in a unique position, however, to do what he did. Like many other Americans at the time, Empey was extremely angry when the Germans sunk the passenger liner RMS Lusitania in 1915. Unlike them, though, he was so mad that he chose to go to London and sign up with the British, rather than wait for America to join the war itself. England was in such dire need that they took him on without complaint, and he went on to serve honorably as an infantry man, a machine gunner, and a bomber, receiving medals for valor in battle until he was discharged due to war wounds. When he was forced to leave the service, Empey dedicated the rest of his wartime efforts to drumming up American support for the war while the war was still being fought.

~*~

-2-

Despite serving in the British Army,

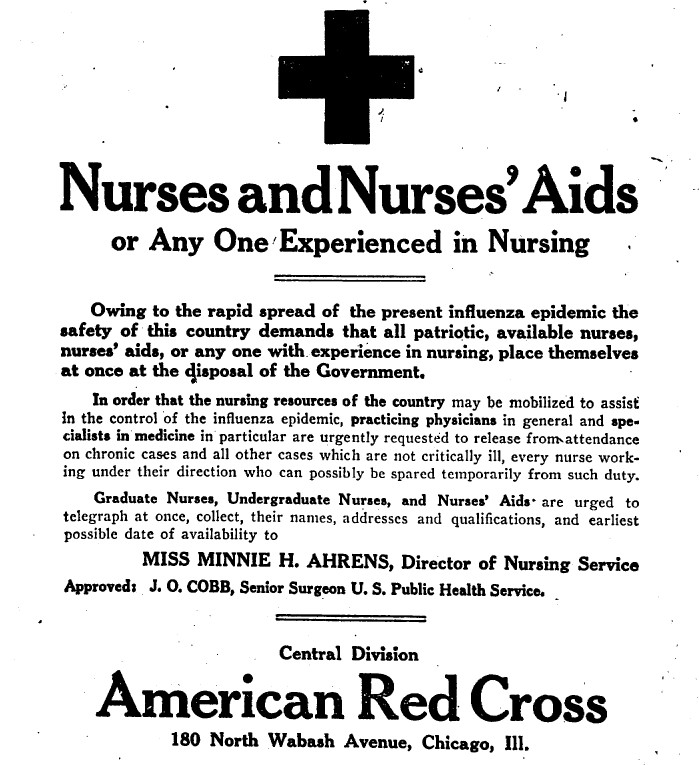

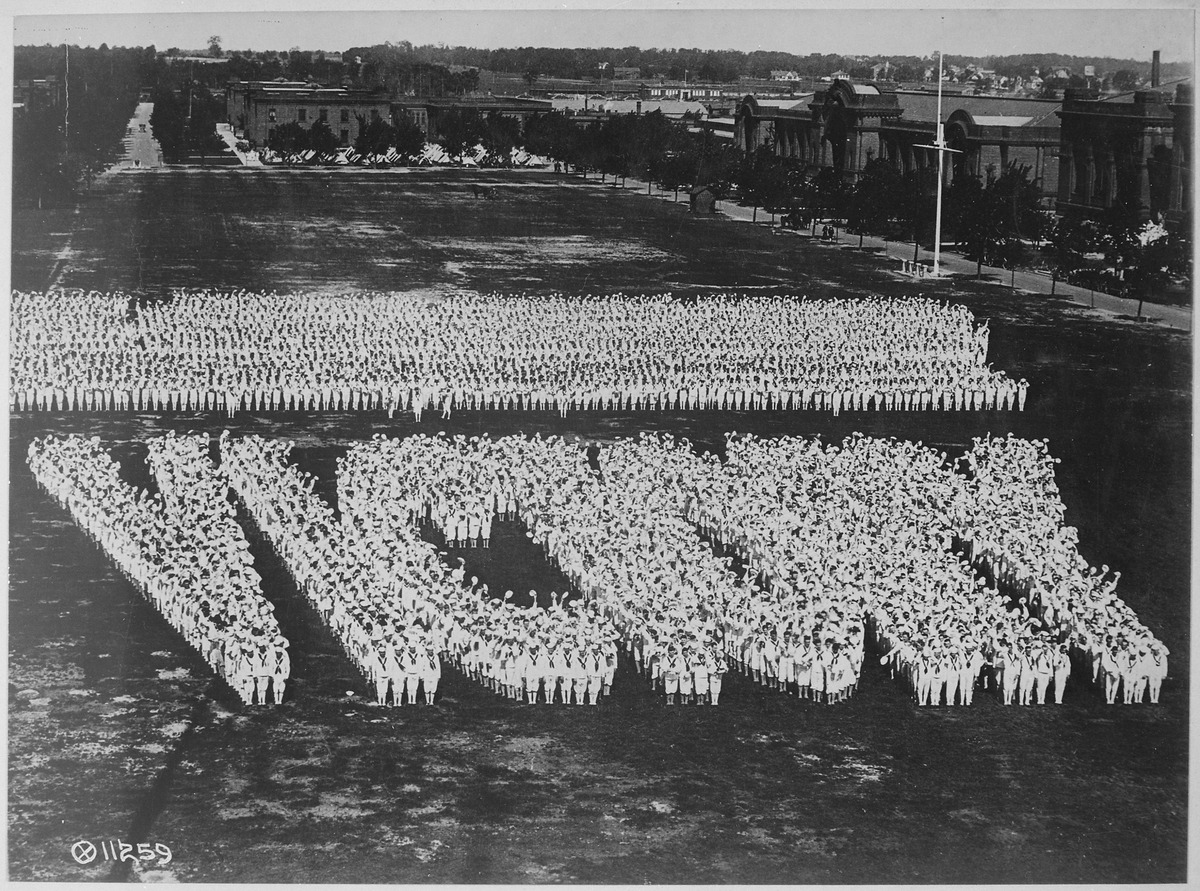

Empey’s book was used as American war propaganda

After his distinguished service in the British Army, the U.S. War Department ended up using Empey’s popular book to encourage Americans to join the Army, buy Liberty Bonds, and stir up general enthusiasm for going to war. Empey was a terrific speaker with a forceful personality, and his honest, direct talk about the war both encouraged men to fight without sugarcoating the whole experience, making him a boon to recruitment and the war effort in general. Empey was happy to participate in this way, as he wrote in Over the Top that he hoped his book would “bring Tommy Atkins” (the slang name for a Tommy, or a common British solider) “closer to the doorstep of Uncle Sam,” and that “Uncle Sam” and “John Bull,” the personification of England, would help one another with the war going forward. As N. P. Dawson notes in “The Good Soldier”: a Selection of Soldiers’ Letters, 1914-1918, Empey’s book was many Americans’ first initiation into the war, and as such he was personally responsible “for a lot of Americans taking a chance at it, and going ‘over the top,’ if not actually, at least with their money and flaming sympathies.”

~*~

-3-

Empey himself was a compelling speaker whose “magnetic” presence

and down-to-earth nature added to the weight of his words

Fanny Butcher, a Tribune book reviewer, seemed to adore Empey as well as his book. They felt his book was “such a downright unembellished record, so truly simple and honest, that I wondered whether the man who wrote it was an artist great enough to tell only the truth or a simple hearted person who sees only the facts of life…a good soldier who by accident had written a big book.”1 When they finally meet him in person, they describe an approachable, down-to-earth everyman—one who might be moreso than the common soldier, if this writer’s description is any indication:

“When I talked to him I realized that I had been right…he is that composite of artist and matter of fact, everyday person…he is an artist in life…You know that he’d be cheerful and slangy and swear if he wants to and smoke a lot of cigarettes and be forceful and have square, stubby hands and not be moony and sentimental about being shot or complain about the rain or night sentry duty. You know that he wouldn’t talk about his wounds or have a bracelet made for his wife of pieces of shrapnel that they took from his body (that seems to be a favorite gift with the returning soldier). You know that he’d be common, in the nice sense of the word. But what you wouldn’t know until you talked to him is that he is gentle and fine and idealistic underneath all that matter-of-factness.”2

Empey was also a “surprisingly riveting speaker,” according to Ron Soodalter at Historynet.com, with “a trick of standing with one foot on the seat of a chair in the middle of a stage, as if he were on the edge of a frontline trench, while he described combat to his listeners. The jagged red scar on his cheek, faint but still perceptible, was evidence of what he had experienced.” A Tribune review of one of Empey’s wartime lectures backs this up, citing not only his performance but the enthusiasm he was capable of drumming up for the war itself:

“A lusty young joker is Empey. Also a mimic. Also a spellbinder and a tip-top showman, stage managing himself with consummate skill. His table and chairs become a trench, his swagger stick now a rifle, now a bayonet. While his uniform, his bomb, his gas mask, and his trench slang are realities, he takes off Tommy and Sandy and Pat with the precision of a finished actor. The audience roars. It cheers. It rocks the house. It has the time of its life….It is the enthusiasm for the war. A lot of sound gospel comes out of Empey’s talk, and every word of that gospel brings a thundering, tempestuous response…Crack the surface, as Empey does, and [war] enthusiasm flames up volcanic. It is tremendous. If ever there was a popular war, a war understood, a war for which Americans cared, it is this war…”3

~*~

-4-

It’s darkly funny, mostly thanks to the bleak humor of English trench life

Empey’s memoir offers many moments of irreverent black humor, something British troops excelled at while stuck in the trenches. Take, for example, his description of “trench pudding,” a “delicacy” that Tommies sometimes made out of desperation:

“is made from broken biscuits, condensed milk, jam—a little water added, slightly flavored with mud—put into a canteen and cooked…this mess is stirred up in a tin and allowed to simmer over the flames…until Tommy decides that it has reached a sufficient (glue-like) consistency…after it has cooled off he tries to eat it. Generally one or two Tommies in a section have cast-iron stomachs and the tin is soon emptied. Once I tasted trench pudding, but only once.”

Somewhat gruesomely, dead bodies were also a source of humor for bored battle-hardened troops. When Empey served as part of a machine gunner group, they took over part of a German trench for their gun and used “a black leather boot”—the foot of a dead German—as a place to hang ammunition. When they lost the foot in a blast of artillery, Empey said he “missed that foot dreadfully…as if I had suddenly lost a chum.” His gunner crew also regularly talked to the corpses sticking up on their side of the line. But this kind of behavior was par for the course: “to civilians this must seem dreadful, but out here, one gets so used to awful sights, that it makes no impression. In passing a butcher shop, you are not shocked by seeing a dead turkey hanging from a hook, well, in France, a dead body is looked upon from the same angle.” Empey also took pains to describe many aspects of daily life for soldiers, some of which were inadvertently funny and sad, such as how soldiers from all ranks would go on a “shirt hunt” together looking for that elusive yet ever-present trench friend, the “cootie,” also known as lice: “It is a common sight to see eight or ten soldiers sitting under a tree with their shirts over their knees…at night…you can see the Tommies grouped around a candle, trying, in its dim light, to rid their underwear of the vermin.”

~*~

-5-

It’s actually a rather emotional memoir given the time period

During a time when men were taught to limit their expressions of feelings, Empey’s book was notable in that he admitted to being deeply affected by the horrors he saw on the battlefield. He also vividly describes his first time going “over the top” in Chapter 11, admitting that he was “sick and faint” at the idea of going up “the Ladders of Death” and into the fray.

This type of direct, emotional language was uncommon at the time even for Americans. According to Doyle and Walker, authors of Trench Talk, it was much more common—particularly for the British soldiers Empey served with—to dance around such topics, and much of the trench slang that Tommies and Doughboys used obliquely references “death, fear and having to attack,” creating many words to describe such things rather than referring to them directly, almost as if “the breakdown of language to adequately describe the physicality of the killing of so many thousands of young men is to be compensated for by a wealth of language for everything surrounding it.”4 In contrast, Empey’s direct language was fresh and bracing at the time, and reviewers claimed it was one of the best parts of his book.

~*~

-6-

He describes the violence of war without glorifying it

Empey was ahead of his time in being realistic about the physical costs and horrors of war as well. While he doesn’t skimp on the gory details, he doesn’t glorify the violence, either. His book is full of simple, to the point descriptions like this one: “I rubbed the mud from my face, and an awful sight met my gaze—his head was smashed to a pulp, and his steel helmet was full of brains and blood.” He pulls no punches when he describes the odor of the dead bodies that littered the battlefield, either:

“the odor from a dug-up, decomposed human body has an effect which is hard to describe. It first produces a nauseating feeling, which, especially after eating, causes vomiting. This relives you temporarily, but soon a weakening sensation follows, which leaves you limp as a dish-rag. Your spirits are at their lowest ebb and you feel a sort of hopeless helplessness and a mad desire to escape it all, to get to the open fields and the perfume of the flowers in Blighty. There is a sharp, prickling sensation in the nostrils, which reminds one of breathing coal gas through a radiator in the floor, and you want to sneeze, but cannot. This was the effect on me, surmounted by the vague horror of the awfulness of the thing and an ever-recurring reflection that, perhaps I, sooner or later, would be in such a state and be brought to light by the blow of a pick in the hands of some Tommy on a digging party.”

These descriptions would have been a helpful preview for potential soldiers, even if they paled in the face of reality.

~*~

-7-

It has some ridiculous stories

One in particular that was often cited by reviewers: a cowardly soldier named “Lloyd” saves his entire troop at the last minute through a dramatic act of suicidal bravery with a machine gun nest. Empey insisted to reviewers and lecture attendees that the story was true, despite how fantastical it might sound. He said he knew the man named Lloyd, that “the psychology of the coward was true as I wrote it,” and that he did in fact die within the time period he gave, for “they found him with the blood still running from his wounds, and blood hardens on wounds almost immediately.”5 Whether true or not, though, it’s a really fun story, and you can find the beginning here—it’s long, but worth it! 🙂

~*~

-8-

There’s a movie!

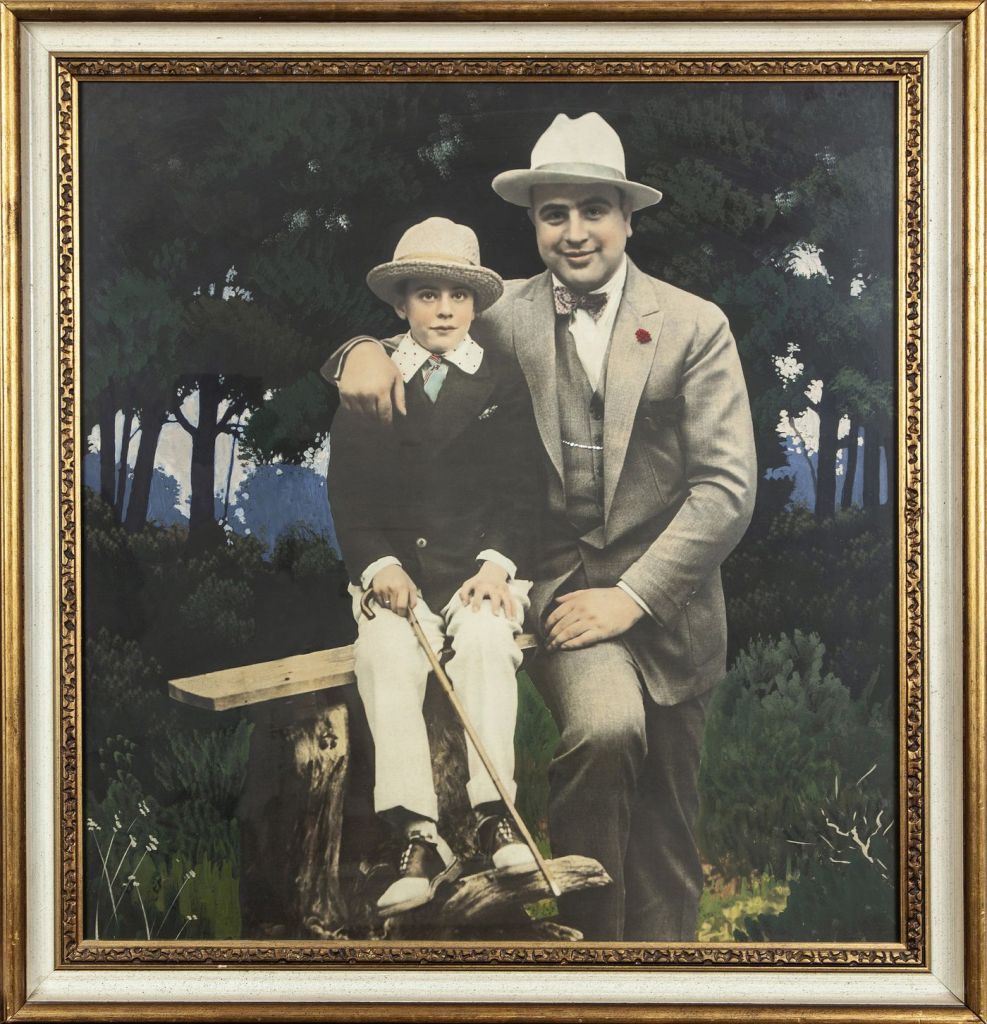

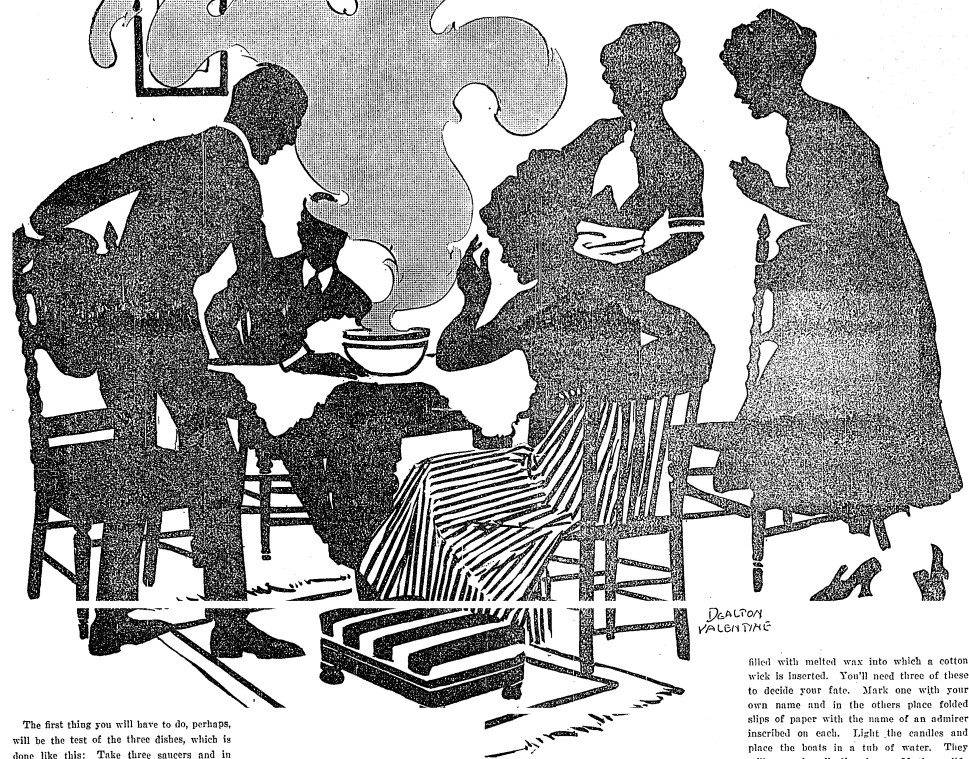

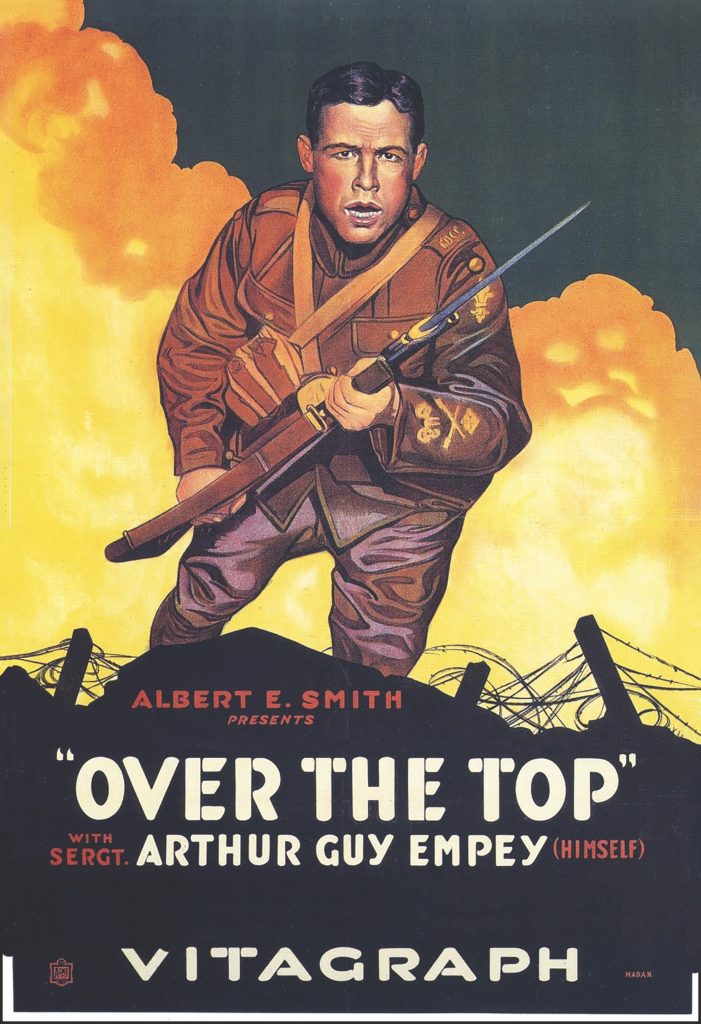

The Vitagraph movie poster for Over the Top (1918)

Empey’s book and lecture circuit were so popular during the war that Over the Top (1918) was eventually turned into a movie by the same name thanks to the good folks at Vitagraph Studios, starring and directed by Empey himself. While Empey wasn’t a film professional by any means, critics praised both the film and his acting. One Tribune reviewer found that Empey’s performance “[rang] true from start to finish,” with “no four-flush nor any suggestion of braggadocio” that one might expect from an amateur.6 None was needed, though, as his “face and body are scarred from the ravages of boche bullets” and “the man who has played a role in the world battle need never fear that he will not ‘get across’ on the screen.”7 Otherwise, the reviewer felt the movie had “punch, action, and a hero who is a real hero,” and audiences seemed to agree, as it performed very well at the box office.8 The movie rights were considered a real scoop for Vitagraph as well, since by that point Empey was highly sought after. By the time the contract was signed, according to Dramatic Mirror of Motion Pictures and The Stage, he’d sold over 250,000 copies of Over the Top in six months, spoke at packed lecture halls all over the country, and had sold over 1 million dollars worth of Liberty bonds thanks to his “magnetic personality.“

The film did so well that Empey went on to found his own production company, called Guy Empey Pictures Corp. or Guy Empey Productions. He went on to write, direct, and star in a number of other silent films, including The Undercurrent (1919), a drama featuring the Red Scare and Oil (1920), a comedy about a cab driver. He also provided the story upon which Troopers Three (1930), a Pre-Code comedy about the U.S. Cavalry, was based. Starring Rex Lease, it’s available to watch for free on YouTube via Part I and Part II.

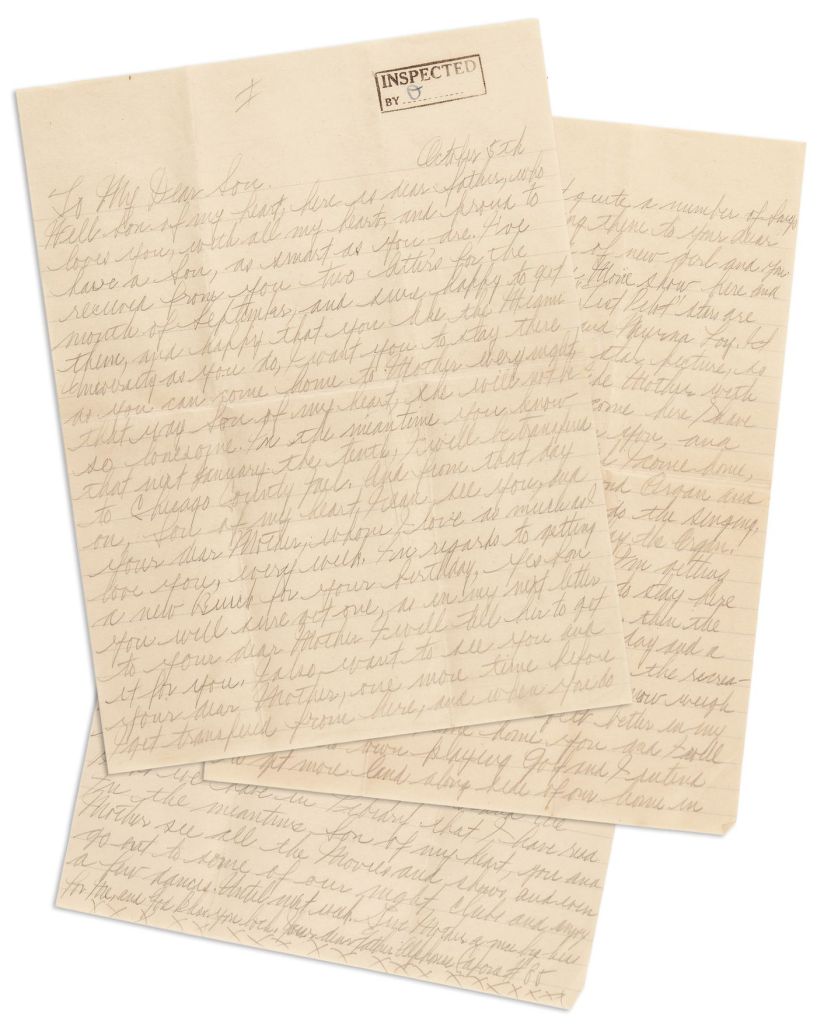

Unfortunately, Over the Top (1918) is one of the many silent films which has been lost to history, but there are a few stills floating around. This one comes from eBay and seems to show trench fighting:

This random still from Over the Top (1918) was recently sold on eBay.

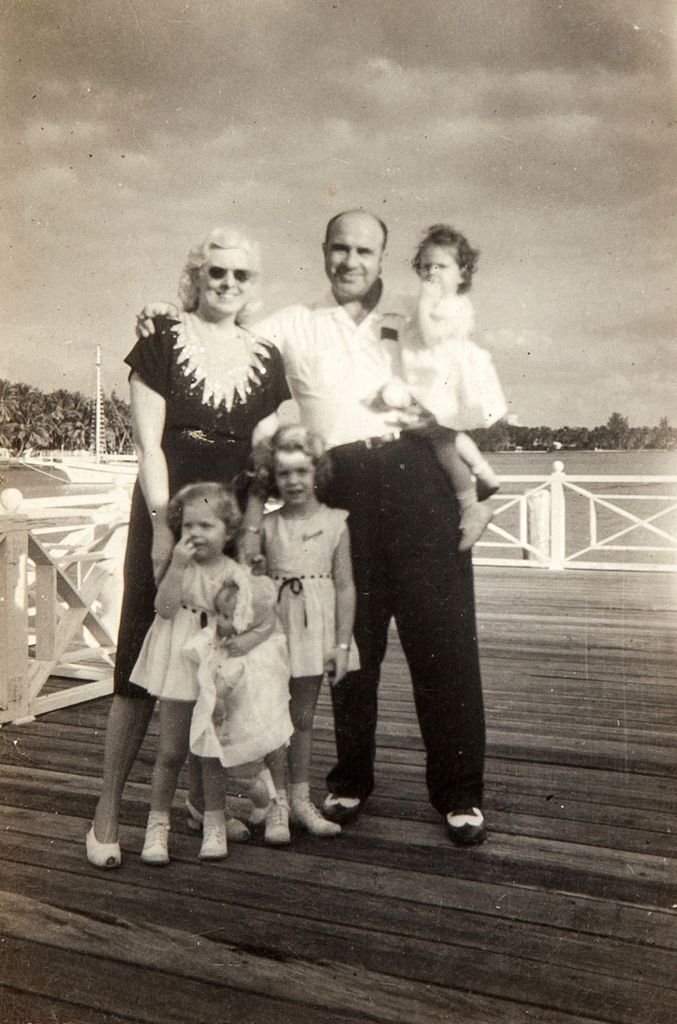

There’s also a nice film still over at Historynet. Looks to me like Empey himself is on the left:

This film still from “Over the Top” comes from Historynet.

~*~

-9-

The WWI slang is terrific!

Empey’s memoir is peppered throughout with actual trench lingo, most of which he forces the reader to learn via context, rather than explain it as he goes. For those who don’t want to figure it out themselves, though, there’s a small dictionary in the back of the book, called Tommy’s Dictionary of the Trenches, which was published separately as well. The slang, as one reviewer puts it, makes it feel even more real: “it’s slangy and frank and doesn’t pretend to be a piece of literature, just a record of one man’s life in the trenches…a man who never says die nor gets sentimental nor forgets his personal and private cuss words.”9 As Emily Brewer points out in Tommy, Doughboy, Fritz, trench slang was a coping mechanism which allowed soldiers to trivialize “the horror witnessed on a daily basis” that was “necessary for maintaining morale,” and helped them describe new weapons and experiences, such as new kinds of artillery fire.10 It also allowed soldiers to bond as a group: they were “proud of their secret language…[which] set them apart from civilians–they had seen and lived through things that those back home could not possibly hope to comprehend.”11

~*~

-10-

He wrote a sequel!

First Call: Guideposts to Berlin (G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1918) , which Empey described as a sort of guidebook for “telling the solider what he’s up against, what to do when he finds himself wounded and lying in no man’s land, how to ask for bread” and so on, was seen as a practical sequel to Over The Top.12 Full of “pages rich with information” where “the dullest facts take on color,” it includes tons of interesting tidbits, such as the fact that “a commonly used method of conveying information by airplanes is by bursts of fire from the machine gun” via Morse code.13 It even includes a small English-to-German dictionary in the back, with fun phrases like “if you attempt to run away, I will shoot you.” So, if you’re looking for another excellent window into daily life for American Doughboys, First Call is worth checking out as well.

~*~

-11-

Empey established a fascist paramilitary group called the Hollywood Hussars

Empey’s life took some strange turns as his fame and his Hollywood career faded during the late 1920s. After writing wartime sheet music during the height of his fame with such catchy titles as “Your Lips are No Man’s Land but Mine” and “Liberty Statue is Looking Right At You,” Empey turned to writing war stories for pulp magazines, including sci-fi, churning out at least 30 during his lifetime.14 After 1930 or so, though, it seems the last notable thing he did was found—I kid you not—an anti-Communist paramilitary cavalry militia called the Hollywood Hussars, which contained folks like Gary Cooper! William Randolph Hearst later insisted that he approached Gary Cooper to start the group with other “he-man film actors” and they were meant to “advertise the charms of a fascist organization to the American public,” while outwardly declaring themselves to be “uphold[ing] and protect[ing] the the principles and ideals of true Americanism.” Either way, it’s a rather strange end to the meteoric rise and fall of Empey’s career.

~*~

WHERE TO READ “OVER THE TOP”

Where can I read Over the Top? You can purchase the book on Amazon here, but why do that when you can read it for FREE here at HathiTrust Digital Library?

Where can I read First Call? The full text of Empey’s “sequel” can be found here at Hathitrust Digital Library as well, or get a 2010 reprint here at Amazon.

Where can I read more about Empey? This article over at HistoryNet is pretty good, and it has way more pictures than my post, plus some information not mentioned here.

~*~